Carl Schmitt Goes to China

A recent article about the resurgence of Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt in Chinese legal circles has set off something of an internet firestorm. Schmitt, for those unaware, is the architect of the Nazi party’s legal strategy and quite possibly the single most dangerous intellectual of the 20th century. His work is heavily influential to a number of leftist scholars of fascism and the state like Walter Benjamin and Giorgio Agamben, who have drawn on his work broadly in order to demonstrate how fascism forms and continues in the modern capitalist state. Other aspects of his work are drawn on by liberal theorists like Claude Lefort as part of what I consider to be a broad counter-revolutionary intellectual project designed to stabilize the modern capitalist democratic state. It was this tradition that caused a number of leftist to simply blow off the article altogether as another piece of pure cold war hack shit, designed to smear the CCP for simply daring to open the work of an intellectual widely engaged with in the West. And to some extent they’re right to do so.

The article itself is absolutely dreadful. Despite his master degree in political theory, Chang Che demonstrates no working knowledge of Schmitt’s theories or the theories of the new Chinese Schmittians, relying instead on snappy quotes from the texts themselves (and at least one line about Schmitt’s affiliation with the Nazis I was unable to source) and one-liners from an assortment of trotted out experts that in no way offer a coherent explanation of what’s going on in the text. Elsewhere Che’s “journalism” is simply laughable. His argument, apparently good enough for The Atlantic, that Chiang Kai-Shek’s alliance with the Nazis is in any way related to the resurgence of Schmitt among Chinese legal scholars and academics would get you failed out of an undergrad seminar. His bizarre attempt to prove some inane point by calculating the number of times People’s Daily said the words “hostile forces” in three completely arbitrary years is likewise frankly just embarrassing. To get an understanding of what’s really going on here you have to read the Chinese Schmittians themselves.

Carl Schmitt, Nazi

So let’s read the damn thing. The most substantially Schmittian of the works Che cites is Chen Duanhong’s regrettably titled On the Particularity of the National Security Concept of Special Administrative Regions under the Condition of "One Country, Two Systems". The article is largely about the difficulties of implementing aspects of the Chinese political system, couched in the language of old socialism, in Hong Kong due to fundamental disputes between the Chinese constitution and Hong Kong common law under the one country, two systems policy. But Chen almost immediately and explicitly begins making Schmitt’s argument that a state has a relative constitution, which consists of the actual written laws of the constitution itself, and an unwritten absolute constitution, unconstrained by written law, that exists to preserve the state itself. The written, relative constitution, both Schmitt and Duanhong argue, is unable to respond to existential threats to national security, which present new dangers that the original writers of the constitution were unable to imagine and thus demand the “dynamic generation” of the unwritten, absolute constitution. That “constitution,” if it can really be called such a thing, is the existence of the state itself and its right to defend itself by the “dynamic generation” of law and order: in essence, the ability to violate and create new laws at will during an emergency. While Chen never mentions it directly, the unwritten absolute constitution and the concept of dynamic generation are based off of Schmitt’s conception of constituent and sovereign power. Here we need to take a step back and look at what constituent power and sovereign power actually are.

The constituent power problem is one of the classical legal paradoxes. As David Graeber put it in his wonderful essay On Batman and the Problem of Constituent Power (printed in full in the conclusion to Utopia of Rules),

But in the modern state, the very status of law is a problem. This is because of a basic logical paradox: no system can generate itself. Any power capable of creating a system of laws cannot itself be bound by them. So law has to come from someplace else... The English, American, and French revolutionaries changed all that when they created the notion of popular sovereignty—declaring that the power once held by kings is now held by an entity that they called “the people.” This created an immediate logical problem, because “the people” are by definition a group of individuals united by the fact that they are, in fact, bound by a certain set of laws. So in what sense can they have created those laws? When this question was first posed in the wake of the British, American, and French revolutions, the answer seemed obvious: through those revolutions themselves. But this created a further problem. Revolutions are acts of law-breaking. It is completely illegal to rise up in arms, overthrow a government, and create a new political order. In fact, nothing could possibly be more illegal.

The constituent power problem is the problem of where laws actually come from. Broadly there’s three solutions to it. One is that constituent power is held by God or another eternal religious entity, which was the original legal solution for why the state holds power in the West (the king is divinely ordained by the God, who created the Law but is not bound by it). Another is that constituent power rests solely in the people themselves, who thus cannot be bound by any other order but themselves directly. This initially seems like an argument for parliamentary democracy (and was seen as such by the liberal revolutionaries who developed it in the French Revolution) but it inevitably leads towards anarchism because as the source of constituent power the people have the ability to simply unmake any law they disapprove of and thus are autonomous individuals who can’t be bound by anything they don’t agree to. The third solution, offered by Schmitt, is that constituent power is held by either an individual or the state because “the people” have invested their authority into that body, which now takes on sovereign power over everyone. Sovereign power is in essence constituent power bound up into a single body. It’s the power to create and recreate an order the sovereign is not bound by, the power to violate the law in order to preserve the legal order itself. It is, in essence, the power to create the “exception” to the rule and govern if necessary by those “exceptions'' alone. It thus represents unbounded dictatorial power with the guise of democratic legitimacy, after all if the people agree to invest their authority into one person then the dictator’s actions are simply the will of the people.

This is the legal justification behind Hitler’s rise to power. As the chancellor of Germany he became the sovereign in order to deal with an “existential threat” to society posed by Jews, communists, the Roma, and the whole litany of Nazi internal enemies, which “justified” a permanent state of emergency and the assumption of dictatorial powers. Scholars like Walter Benjamin and Ambagen argue that the permanent state of exception, where the written laws of the legal order are tossed aside for an emergency and the state wields unchecked power that can be invoked through the sovereignty of the state is the core of fascism itself. Dynamic generation, the principle behind the absolute constitution, is nothing more and nothing less than the exercise of sovereign power through the power of the state of exception invoked during states of emergency. But where leftist theorists like Benjamin argue against the state of exception and warned of its dangers, Chen Duanhong does the exact opposite, arguing that the ability to invoke the absolute constitution against the written laws of the relative constitution, thus bringing society into a state of exception, is actually a good thing and is in fact the reason why Beijing can exercise its national security powers in Hong Kong in direct contravention of their own written laws. “The existence of the country is first,” Chen writes, “and the constitutional law must serve this fundamental purpose. On the other hand, the effectiveness of the constitution comes from the constitutional power [the absolute constitution], which is not restricted by law.” This is a direct argument for the sovereignty of the state, unbound by its own laws and free to exercise its emergency powers as it wishes.

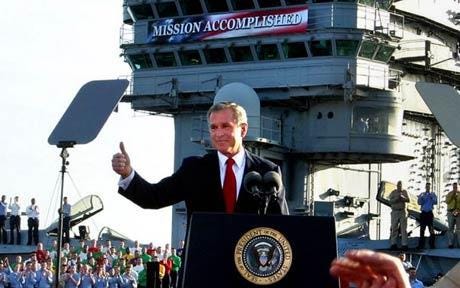

Now I obviously don’t think China is about to literally become Nazi Germany. But there’s another danger in Schmitt’s writing that opens a path we’ve already seen countries go down in the 21st century. Attentive readers might have picked out the similarities between the rhetoric of national security and existential threats found in Chen’s writing and kinds of legal and political arguments Bush, Cheney, and the neoconservatives made in the wake of 9/11. Theorizations of the War on Terror, especially in its early years, focused heavily on the state of exception the US government invoked to do everything from rounding up Muslims in the streets of New York to torturing prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. The boldest among them argued that the War on Terror and the permanent state of emergency in which we all live is a form of fascism. The greatest danger to Chinese society posed by Schmitt’s work is its use to justify a Chinese war on terror, and, unhappily, that war on terror has already begun. The state of emergency that’s been active in Xinjiang since 2014 is quite literally called The People’s War on Terror. What followed was a campaign of mass surveillance and repression that ultimately culminated in China’s own ghastly mirror of the forced labor brigades created by the US army after the siege of Fallujah and the massive prison at Camp Bucca. The CCP even imported America’s own homegrown Evangelical fanatic mercenary Erik Prince to do counter-insurgency training for Chinese military personnel and police officers. The real danger, then, is not that China becomes Nazi Germany by way of Nazi legal theorists. The danger is that, through joining the global war on Muslims, China becomes the US. That process, now buoyed by Schmitt’s extremely dangerous legal theories, has already begun. It is our task to unmake both systems, to ensure that the fusion of state and capital can never again lurch down the path towards the permanent state of exception. If we fail, history has already shown us what follows.